“Suffering the loss of her liberty, the lark, a delicate songbird, will no longer sing her little heart out. Her tyrant, the man committed to her imprisonment, may pressure, and even torture the bird to comply to his wishes and change herself to suit his pleasure or benefit. And still, the lark will refuse.” – Bobby Sands

Es durante las experiencias más sombrías de ocupación y apartheid que nosotros, los palestinos, buscamos la esperanza dondequiera que se encuentre, y al hacerlo, nos consideramos verdaderamente afortunados de tener amigos de origen irlandés. Una mirada a la imagen de un pueblo irlandés adornando cada calle y pub con la bandera palestina junto a la suya propia... es el tipo de apoyo desafiante hacia el prójimo que puede alimentar nuestro espíritu palestino de ver el vaso medio lleno, una inspiración profunda y una fortaleza en la que nos sustentamos con frecuencia.

Hasta el día de hoy, el pueblo irlandés es el defensor europeo más enérgico de los derechos palestinos a la libertad y autodeterminación. La conexión espiritual entre estos dos aliados geográficamente distantes y sorprendentes no es una coincidencia. ¡La memoria y las consecuencias de la colonización viven en la esencia misma de cada hueso irlandés!

Tá mo scéal amhlaidh – Irish History with Colonialism

Residing in the ever-green rolling hills of their homeland for more than 10,000 years, the Irish, Gaelic in origin, share ancient customs, language, music, dance, and mythology that have made their culture unique to that of their European neighbours. Yet like Palestine, the country of Ireland was tragically partitioned – one people split into two states – at the outset of the 1919-1921 Irish War of Independence against the British Empire.

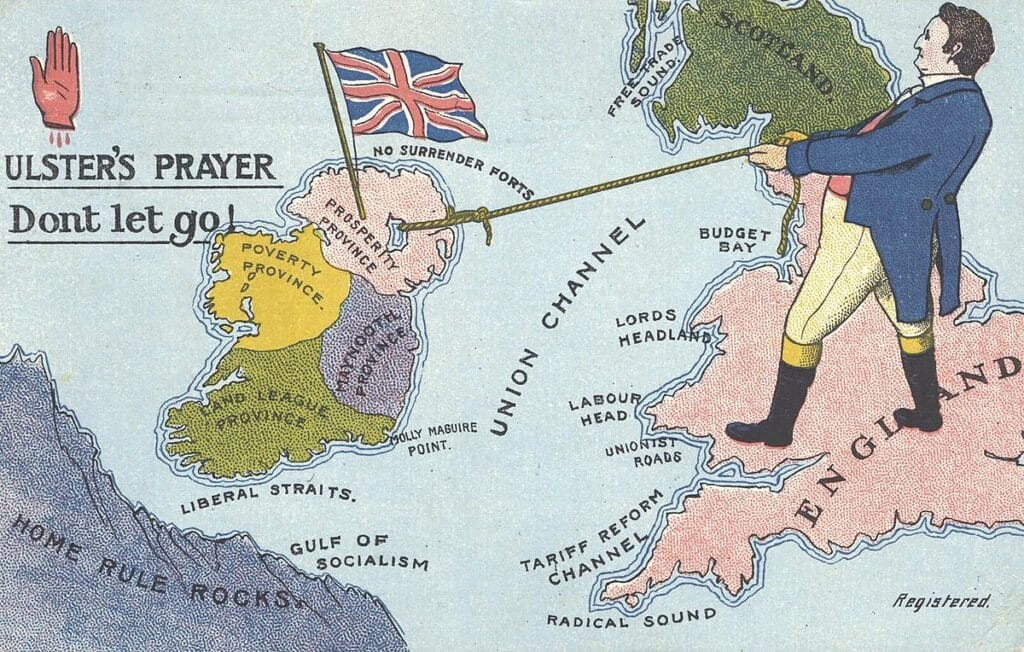

The Irish struggle against British colonial rule goes as far back as the 1600s, when a hundred-year struggle for Irish liberation from its British invaders, came to a head with the devastating scorched-earth campaigns of British General Oliver Cromwell, who’s colonial army massacred or starved anywhere between 15 to 83 percent of the Irish population.

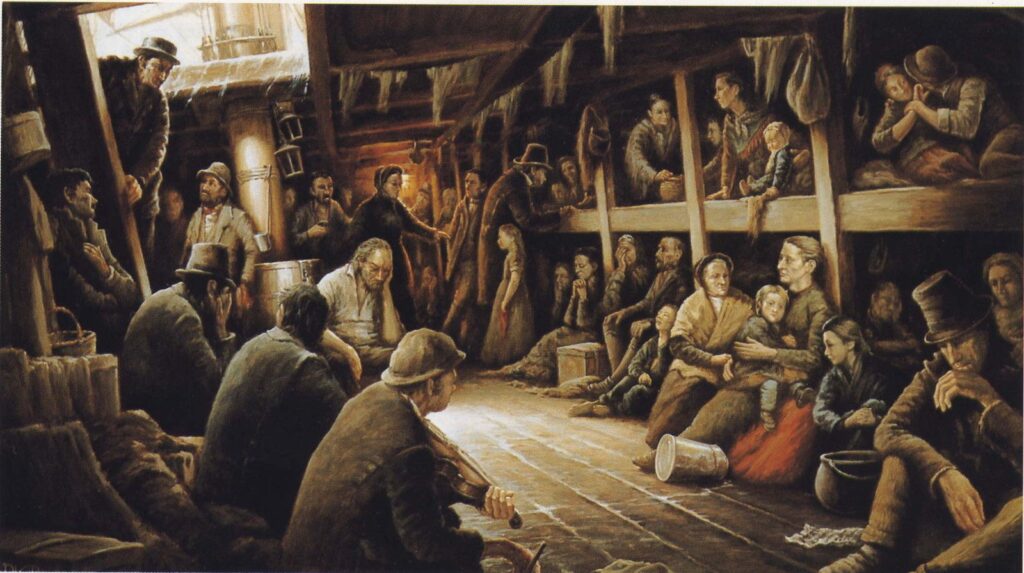

Then there was the infamous Great Potato Famine of the 1800s, wherein starving Irish folk, enduring years of poor harvest, were nevertheless obligated to export their grain to their British rulers.

An estimated two million Irish people consequently died of starvation, and two million more left the country, migrating to the Americas and elsewhere to form what is to date one of the largest diasporas in the world, around 50-80 million people globally.

Such brutal colonialism culminated with the 1900s Irish War for Independence and the later “Troubles”, a long period of anti-colonial resistance, and eventually warfare between Irish factions, instigated by the divisions made manifest during British occupation.

Throid mé ar son mo Saoirse – The Fight for Freedom

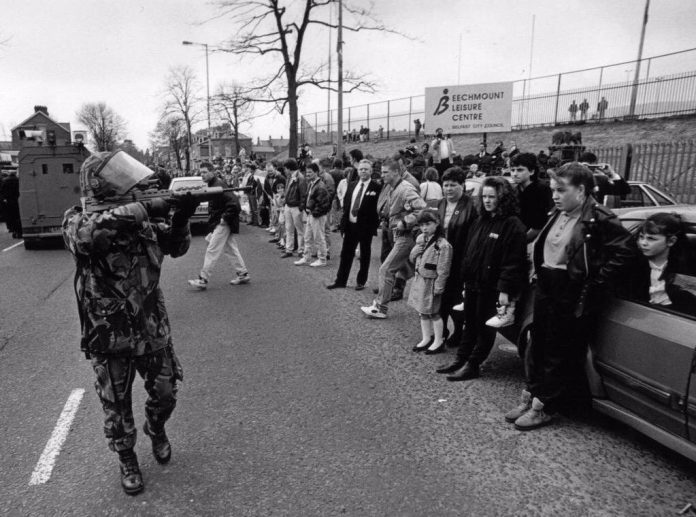

Reading the historic details, one quickly learns that the shared experience of Irish and Palestinian people under occupation runs remarkably deep. Responding to the revolutionary fervour of the Irish, the British Empire deployed the now notorious “Black & Tans”, a military unit of 10,000 men ordered to punish any resistance with ruthless acts of violence against innocent Irish civilians.

In the aftermath of the war, British forces were eventually withdrawn, and the Irish until today jokingly ask, “What happened to the Black and Tans?”. The bleak truth is a large number of them eventually went over to Palestine and were used by the British to brutally oppress the Palestinian people.

That’s not all. Before his escapades dictating the fates of colonised Palestinian people, Arthur James Balfour (responsible for the disastrous Balfour Declaration) had previously held a seat as chief secretary for Ireland on behalf of the British Empire and had busied himself with the repression of Irish activists and boycotts, imprisonment of over 20 Irish members of parliament without jury, and was giving orders for guns to be fired into crowds of Irish demonstrators – earning him the nickname “Bloody Balfour”.

The connected experience of Ireland and Palestine is captured perhaps most acutely by the issue of Political Prisoners. Under British Mandate in Palestine, the British occupiers introduced Administrative Detention, which allowed for the imprisonment of Palestinian “non-conformists” for indefinite periods of time without trial or charge – a law used by Israel to this day, through which over four thousand Palestinians are unfairly imprisoned.

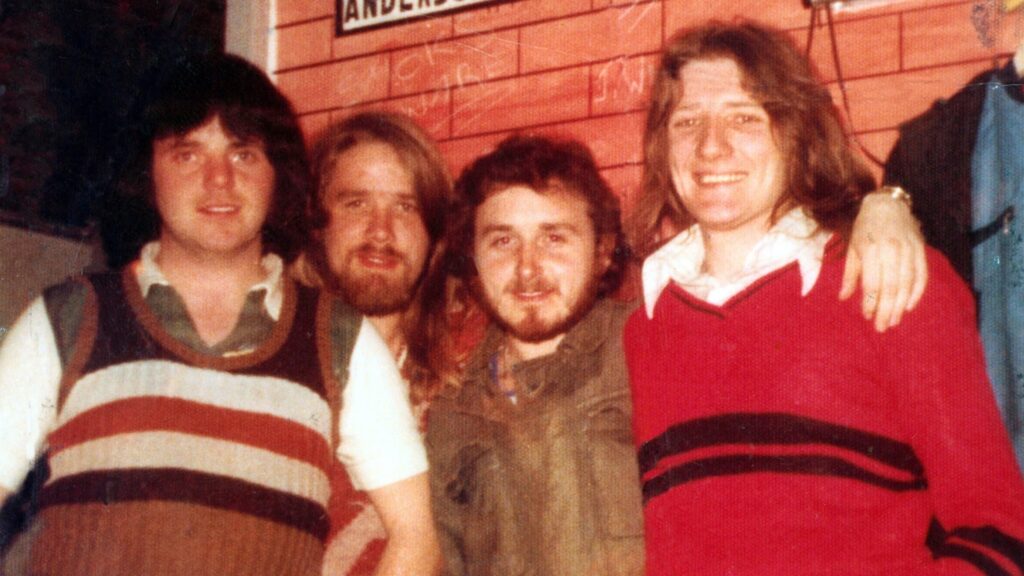

Similar laws introduced in the north of Ireland in 1971, with the intention of imprisoning IRA members, led to mass arrests of almost 2000 people, most of whom had no connection to the IRA. Behind bars indefinitely, many resorted to hunger strike, an act now defiantly adopted by thousands of Palestinian prisoners, as a “battle of empty stomachs”, (examples include Hisham Abu Hawash, Ghadanfar Abu Atwan, and many more). Many died in Ireland, including Irish MP Bobby Sands and his republican compatriots, starving themselves in resistance to their indefinite incarceration. Sands captured the imagination of Palestinians and Irish people alike in his tale of the Lark and the Freedom Fighter, in which he describes a songbird and its unwillingness to sing to its captors, to the point of its eventual death. “I feel something in common with that poor bird”, wrote Sands.

After Sands death on May 5, the 66th day of his strike, Palestinian prisoners in Israel’s Nafha prison smuggled out a letter in support of the Irish hunger strikers. It read: “We salute the heroic struggle of Bobby Sands and his comrades, for they have sacrificed the most valuable possession of any human being. They gave their lives for freedom.” (Yousef M Aljamal, 2021)

Agus inniu mé ag troid ar do shon – Irish Unity with Palestine

The connection between Ireland and Palestine, which transcends religion, ethnicity, and geography, would be nurtured, and shared rather by lived experience of the struggle for freedom. And that fire of liberty burns still. Last summer of 2021, following the atrocities of the Gaza bombings, the Irish Parliament (Dáil Éireann) voted unanimously to condemn the building of illegal Israeli settlements in the Palestinian territories as “de facto annexation”.

The Irish Parliament captured international attention in 2018 when it passed the Occupied Territories Bill, which would have boycott and banned all goods and services originating in illegal settlements in the West Bank. Yet from the outset of its declaration, US political powers on the behalf of Israel swiftly intervened, warning that commercial relations between their countries would be “adversely affected” by the passage of the bill, therein obliging Irish politicians to choose between obeying the Irish law or United States anti-boycott legislation. The Occupied Territories Bill had been effectively blocked.

Yet the fight is not over, and Irish solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for freedom is perhaps stronger now than ever before. Ireland remains at the vanguard in defending Palestinian rights and holding Israel to account for its crimes and oppression.

Renowned Irish novelist Sean O’Faolain, expressed in 1947 the sentiment: “if we could imagine that Ireland was being transformed by Britain into a national home for the Jews, I can hardly doubt which side you would be found.”

Irish Foreign Minister Frank Aiken described the issue of Palestine as the “main and most pressing objective” of Ireland’s Middle East policy. By the time Aiken left office, Irish policy was set in stone: There could be no peace without the repatriation of the maximum possible number of Palestinian refugees and full compensation, not merely resettlement, for the remainder (Rory Miller, 2010)

Undoubtedly, the people of Ireland have set a course for other countries to follow suit. For countries around the world to take that stand against the apartheid system that Israel perpetrates, and stand by the right to liberty for all; the sacred right to determine one’s own destiny.

To our friends of Eire, we dedicate the Saoirse Kufiya to you, devoted to “liberty” and “freedom” in the Irish Language. Inspired by the words of Bobby Sands; a lark need not change to regain her liberty, nor does it wish to change, and if it is fated to die, it will die making that point.

Palestinian Kufiya Dedicated to the Irish People

For the first time ever, we’re dedicating a Kufiya to a location outside of Palestine. A home of an incredible people, whom we as Palestinians are so proud to call our friends – the Irish.

We’ll be creating more kufiya designs this year dedicated to the people of Countries we love.

Which country should we design a kufiya for next? Email us and let us know your ideas!

Saoirse Irish Hirbawi® Kufiya

Presentamos "Saoirse", una Kufiya hecha en Palestina que abraza los colores vibrantes de la bandera irlandesa. Esta Kufiya única es un símbolo de libertad y emancipación, llevando el nombre "Saoirse" (pronunciado seer-sha) en el idioma irlandés. Es un sincero homenaje al espíritu resiliente del pueblo irlandés. Con su diseño distintivo y simbolismo significativo, "Saoirse" encarna los valores compartidos de determinación, independencia y herencia cultural. Luce con orgullo esta notable Kufiya, celebrando la conexión entre Palestina e Irlanda, y el anhelo universal de libertad.